A law school steeped in tradition, the Faculty of Law of the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena de provides the best conditions for study for its currently approx. 2,000 students. This is reflected in the Faculty's renewed achievement of a top position in the current CHE ranking for 2017/18. The Faculty was particularly positively evaluated by its students in the categories of choice of courses, study feasability and international and academic relations. But the faculty was not just convincing from an academic point of view: the social climate as well as the supervision and support during their studies also contribute to students' feeling of well-being in Jena.

Law in Jena:

What happend so far.

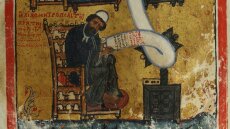

Starting boldly. Legal scholars, with their own law faculty, were among the founders of our university, which was built between 1554 and 1558 in the Collegium Jenense. It was inaugurated by imperial preorgative of Ferdinand I. as a Saxonian-Ernestine state university, after Wittenberg (with its university) had fallen to the Saxonian-Albertine line of the Wettins in 1547 and was "lost" to the Ernestine rulers. At the centre of academic teaching was the jus commune - and with it the central question of the 16th and 17th centuries, namely how to deal with the differences between this Roman-based law on the one hand and the local law, which was largely based on the Sachsenspiegel, on the other. This also led the legal scholars of the early Jena university (e.g. Gregor Brück, Basil Monner, Virgil Pingitzer and Matthias Wesenbeck) out of the lecture hall. They were not only university teachers, but judges, privy councillors, educators of princes, and conciliar and consistorial lawyers. The law faculty was itself a court and its members also provided Jena's magistracy (Schöffenstuhl), the High Court (Hofgericht) in Jena, and the sovereign's chanceries and consistories with knowledge and personnel. Whoever needed legal advice - courts, rulers, lawyers, litigants - turned to the faculty. Its professors were in the middle of the Europe-wide exchange of legal ideas inspired by the Jus Commune and helped draft early modern laws (e.g., in the case of Matthias Wesenbeck, the "Kursächsische Konstitutionen"). The founders were also associated with Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon and the Ernestine Saxon electors/dukes. In 1530, Gregor Brück formulated the "Augsburg Confession" of the Protestant imperial estates, co-founded the Schmalkaldic League and so took a Protestant axe to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. In 1557 he was involved in the enlargement of a grammar school into a university/faculty.

Sticking with it. Jena's legal education and scholarship in the 17th and 18th centuries were embedded in the process, accelerated by the religious schism, in which the German Empire dissolved into its territories. The doctrine of sovereignty, which granted the individual prince comprehensive power of the state in his territory, was mainly supported in Jena by Dominik van Arum and his student Johannes Limnäus. Both uncoupled legal thinking on constitutional law from Roman law and developed their own doctrine of constitutional law based on the constitutional reality of the empire. Many graduated from the Faculty to serve as experts for the surrounding territorial dominions, thus strengthening them. The usus modernus Pandectarum, which gave the local law an autonomous position in relation to Roman law, also established itself in the Faculty in the second half of the 17th century under the auspices of Georg Adam Struve - for many years professor, dean, rector and privy councillor. Struve's influence was far-reaching: his "Iurisprudentia Romano-Germanica forensis" was a standard legal textbook - beyond as well as within Jena - for more than a hundred years from 1670. Nor were natural law and legal encyclopaedias absent from Jena: Gottlieb Hufeland advocated them both. And, moreover, Friedrich Schiller knew this!

Making it big. Jena's "Sattelzeit" around 1800 was pregnant with modernity. Between 1790 and 1810, the great movers of German intellectual life - including lawyers - gathered in Jena. Friedrich Carl von Savigny, the founder of the Historical School, which dominated jurisprudence in the 19th century, did not hold a professorship in Jena, but he stayed here several times for extended periods, and his greatest adversary in the codification dispute, Anton Friedrich Justus v. Thibaut, taught Roman law in Jena. Thibaut's work Über die Notwendigkeit eines allgemeinen bürgerlichen Rechts in Deutschland ('On the Necessity of a General Civil Law for Germany') (1814) caused Savigny, to write his reply Vom Beruf unserer Zeit für Gesetzgebung und Rechtswissenschaft ('Of the Vocation of our Age for Legislation and Legal Science'). The Jena scholarly republic sparkled and also ignited the brightest star in the Jena legal sky: Paul Johann Anselm Feuerbach. In sharp contrast to the early modern theory and practice of poena arbitraria, he formulated the principle of nulla poena sine lege and, with his concept of "psychological coercion", he freed the science and legislation of criminal law from the focus on the sole retribution of injustice.

Taking a breather. The great start at the beginning of the 19th century could not be sustained consistently in teaching and research afterwards; none of the academic teachers of the second half of the 19th century comes close to Thibaut and Feuerbach in scholarly importance. Carl Friedrich v. Gerber, the founder of positivism in constitutional law and later Saxony's Minister of Culture, had at least gained merit with one of the leading teaching books on "German private law" before his call to Jena in 1862 (which he was soon to give up for Leipzig). Representatives of the Germanist branch of the Historical School contrasted such treatises with the Romanists' Pandectist textbooks, thereby translating the German-nationalist enthusiasm of the 19th century with its patriarchal stance into civil law principles, doctrines and constructs. The diamond of German jurisprudence and legislative technique, the BGB, was not, however, shaped by Jena professors themselves. (The Jena Extraordinarius Johannes Conrad, member of the second BGB commission, was a national economist, not a lawyer.) At the end of the 19th century, compared to other law faculties in the empire, the faculty was a small institution of rather regional importance. It also had to struggle with the fact that the four states supporting the university were not always able to provide solid funding.

Overhauled. The last years of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, however, changed the Faculty. From 1917, the Faculty had an influential conservative "think tank", the Institute for Business Law, under the aegis of Justus Wilhelm Hedemann, from which Hans Carl Nipperdey emerged and qualified as a professor in Jena. This innovative project was decisive in securing the existence of the Faculty. Nipperdey repeated the Jena institute model later in Cologne and had a decisive influence on labour law and legislation even in the Federal Republic. The same applies to Alfred Hueck, who held the Jena Chair of Commercial, Labour and Corporate Law from 1925 to 1936. In 1923, the Faculty was expanded to include the field of political economy (which was carved out of the Faculty of Philosophy) and thus became the "Faculty of Law and Economics". At the same time it was divided internally into institutes and seminars with a total of nine chairs. Labour law, business administrative law, insurance law and thus also social security law became established in teaching and research. Thus, once again Jena was able to provide impulses for development, both in these and other fields of law. The Free State of Thuringia, which was formed in 1920 from several previously independent states, owes its first republican constitution to the Jena constitutional lawyer and legal historian Eduard Rosenthal, and the last major citation-rich classic on "German Private Law" was penned by the Jena legal historian Rudolf Hübner.

Fuelling the fire. The Faculty joined the National Socialist "awakening", which was to lead to social and moral collapse, and in turn helped accelerate it after having already awarded a doctorate for a thesis on labour law in 1922 to the man who was later to become the most infamous hanging judge of the Nazi state, Roland Freisler. Jewish and "politically unreliable" colleagues, mainly from the economics branch of the Faculty (such as the unscheduled Professor of Civil, Procedural and Labour Law and Marxist, Karl Korsch, who had in fact already emigrated - and thus departed just in time, or Berthold Josephy, the Professor of Political Economy), were dismissed or pre-empted theirimminent dismissal (such as the Professor of Economic Statistics, Paul Gustav Ritter v. Hermberg, who after the Nazi seizure of power was retired at his own request and likewise emigrated). Doctoral degrees which had been validly acquired were annulled for racist and political reasons. Professors who were active in the Faculty after 1933 advocated positions rooted in an ethno-nationalist, German common law (Ulrich Scheuner, Carl August Emge, Richard Lange). In 1937, the professors active at that time (with three exceptions) joined the NSDAP. Even before 1933 Otto Koellreutter, Professor of Constitutional and Administrative Law in Jena since 1921, had already been one of the sharpest conservative (and soon openly National Socialist) critics of the Weimar state. Justus Wilhelm Hedemann, Günter Haupt, Carl Emge, Ulrich Scheuner, Karl Blomeyer worked at the Academy of German Law (AfGl) on the drafts of a Volksgesetzbuch and other legislative projects. However, they were reticent about the plans for reform of legal education. One expression of the orientation of the University of Jena along völkisch "law of life" lines under Rector Karl Astel, which also permeated the Faculty of Law and Economics, was the creation in 1940 of a new chair for "Race and Law", to which Falk Ruttke was appointed. He gave legal forms to the theory of racial hygiene and heredity, helped to shape racial legislation, provided commentary on the Law for the Prevention of Gentically Diseased Offspring, and worked in the AfGl. In 1941, the Rector recorded that the university had "become the first university in Greater Germany geared towards racial and life laws". The professors of the faculty deliberately participated in this and so helped shape one of the main socio-political projects of the National Socialist "movement".

On an "historic mission" for the working class. After the end of the war and during the administration of Thuringia by the Soviet Military Administration (SMAD) lectures were not suspended, but in the winter semester 1945/1946 there were only three professors left. Teaching staff had died in the war, migrated to the West, fled from Germany or been suspended (e.g. the Dean in 1935, Hermann Schultze-v. Lasaulx). The SMAD and later the SED-led university administration of the GDR strove to train and recruit new staff committed to the "historical mission of the working class". In doing so, they sometimes "missed the mark", as in the case of Gerhard Buchdas, who until 1967 advocated a traditional, bourgeois legal history. The "Third Higher Education Reform" (1967-1972) completed the program. In 1968 the Faculty was closed and its institutes were dissolved. For three years no students were matriculated. Some of the staff switched to the "Department for Political Science and Law", which was founded in 1971 and was part of the university's new "Faculty of Social Sciences". The Department played an important role in socialist political and legal science and in the education of socialist-thinking lawyers.The SED's plans envisaged that mainly future prosecutors would be educated in Jena. Whether that was implemented - and whether therefore the professors of the Department for Political Science and Law supported the politicised justice of the GDR - has not yet been sufficiently researched. Admission to study law and political science, the contents of the courses and grading were regulated uniformly throughout the GDR; often no more than 25 selected students per year began legal studies in Jena. The topics of the doctoral theses reflect the academic reorientation. Moreover, professors in Jena were involved in law-making. Martin Posch drafted parts of the civil code of the GDR, which was to implement the ideologically defined political goals of the "party of the working class". Gerhard Haney and Gerhard Riege formulated central theses of a socialist political and legal science that was built not on individual rights and freedom, but on the assumption of "socialist state power under leadership of the Marxist-Lenninist party", that "its authority and its functional capability [was] the basis and the prerequisite" for "historically deterministic advancement", and that socialist law should educate the "workers to conscious adherence to socialist legal norms, to conscious discipline and vigilance, to stricter adherence to the socialist legality and to safeguarding security and order". In the 1980s, Martina Haedrich and Annemarie Langanke became the first female law professors (of international law and of labour law) in Jena.

Starting over again for freedom's sake. After the peaceful revolution, the Department sought to transform itself into a faculty in 1990. To that end, decisions were initially made at university level. In contrast, the Thuringian state government and the management of the Friedrich Schiller University, now dominated by those intent on renewal, favored an organizational clean break that would almost completely replace the teaching staff. They decided to "wind up" the Department. For an interim period, the teaching activities were maintained; professors from Marburg and other faculties prevented a teaching vacuum. In order to be able to re-establish a faculty, new structures were developed; chairs were newly established and filled. In autumn 1992, the Faculty of Law, which exists today and is committed to the same law, academic freedom and free debate, was opened.

Adrian Schmidt-Recla, Jena/Leipzig

Sources:

Blau, Günter, Paul Johann Anselm Feuerbach, Berlin 1948

Hattenhauer, Christian/Schroeder, Klaus-Peter/Baldus, Christian (Hrsg.), Anton Friedrich Justus Thibaut (1772-1840). Bürger und Gelehrter, Tübingen 2017

Lingelbach, Gerhard/Krahner, Lothar (Hrsg.), Gedächtnisschrift für Gerhard Buchda, Jena 1997

Lingelbach, Gerhard, Eduard Rosenthal (1859-1926). Rechtsgelehrter und "Vater" der Thüringer Verfassung von 1920/21, Weimar 2008

Lingelbach, Gerhard (Hrsg.), Rechtsgelehrte der Universität Jena aus vier Jahrhunderten, Jena 2012

Opitz, Jörg, Die Rechts- und Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Jena und ihr Lehrkörper im "Dritten Reich", in: Hoßfeld, Uwe/John, Jürgen/Lemuth, Oliver/Stutz, Rüdiger (Hrsg.), "Kämpferische Wissenschaft". Studien zur Universität Jena im Nationalsozialismus, Köln u. a. 2003, S. 471-518

Rosenthal, Walter (Hrsg.), "Ein Unrecht, das nicht weiterwirken darf." Die Entziehung von Doktorgraden an der Universität Jena in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, Jena 2016

Rückert, Joachim, Friedrich Carl von Savigny. Leben und Wirken (1779-1861), Köln u. a. 2011

Schmidt-Recla, Adrian/Gries, Zara Luisa, Getaway into the Middle Ages? On topics, methods and results of "socialist" legal historiography in Jena, in: Erkkilä, Ville (ed.), Socialism and Legal History. The Histories and Historians of Law in Socialist East Central Europe, Abingdon/Oxfordshire 2020 (in print)

Schmoeckel, Mathias, Dominik Arumaeus und die Entstehung des öffentlichen Rechts als rechtswissenschaftliches Lehrfach in Jena, in: v. Friedeburg, Robert/Schmoeckel, Mathias (Hrsg.), Recht, Konfession und Verfassung im 17. Jahrhundert. West- und mitteleuropäische Entwicklungen, Berlin 2015, S. 85-127

Steinmetz, Max (ltd. Hrsg.), Geschichte der Universität Jena 1548/58-1958. Festgabe zum vierhundertjährigen Universitätsjubiläum, Bd. 1, Jena 1958

Stolleis, Michael (Hrsg.), Juristen. Ein biographisches Lexikon. Von der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, München 2001

Weingart, Peter/Kroll, Jürgen/Bayertz, Kurt, Rasse, Blut und Gene. Geschichte der Eugenik und Rassenhygiene in Deutschland, 2. Aufl., Frankfurt/M. 1996

Zeumer, Johann Caspar/Weissenborn, Christoph, Vitae Professorum Theologiae, Iurisprudentiae, Medicinae et Philosophiae qui in illustri academia Ienensi ab ipsius fundatione ad nostra usque tempora vixerunt et adhunc vivunt, Jena 1711

The facts speak for themselves:

The Faculty of Law today

University professors and staff in a total of 18 chairs plus three lecturers ensure a broad range of courses with an excellent staff-student ratio. In addition, the Faculty is supported by numerous honorary professors, private lecturers and assistant lecturers, who enrich and expand the teaching program with great commitment.

The Faculty enjoys a very good position in teaching and research throughout Germany and beyond. It aims to establish itself permanently among the leading law faculties in Germany and Europe. Within the ranking of the Centre for Higher Education Development (CHE), the Faculty of Law regularly occupies top positions, which also underlines its competence in comparison to other faculties of law.

The Friedrich Schiller University is one of the oldest universities in Europe and is steeped in tradition. Together with the Universities of Göttingen, Heidelberg and Würzburg, it belongs to the Coimbra Group, an organisation of mature European universities of high international standing.

Reaching the destination without detours

The Faculty of Law is ideally located in the centre of Jena and students enjoy the shortest of paths in their learning environment. The modern building complex houses the Faculty's administration as well as its chairs and institutes. Most of the modern equipped lecture halls and seminar rooms used by the Faculty are also located here.

In addition, the Thuringian University and State LibraryExternal link is represented in the building complex with its Law, Economics and Social Sciences section. Finally, the building also houses the Faculty's computer pool with 100 modern workstations.

Profile in teaching

The teaching of law is characterised by the aim of providing young lawyers with comprehensive training for their later professions and guiding them to the first examination. The teaching profile of the faculty is characterized by a research-based transfer of knowledge and skills that enables students to think and work independently. Legal education in Jena incorporates the basic subjects in their diversity and sets strong accents in education in specialist subjects.

The Law & Language Center's lecture programExternal link, which introduces students to foreign legal systems in English, French, Spanish and Russian, should also be emphasized.

In addition, the Faculty of Law has made a name for itself, both nationwide and internationally, through the successful participation of its students in various moot courtsExternal link.

Currently, the Faculty of Law offers three undergraduate and four postgraduate programmes of study:

Undergraduate study programmes

- Law with the First Examination (until 2006 First State Examination in Law)

- The Legal Part of the Subject Economics / Law for the Teaching Profession at Grammar Schools according to the Jena Model

- Law as a Supplementary Subject with the Degree Bachelor of Arts

Postgraduate study programmes

- Private and Public Commercial Law (LL.M. oec.)

- Law for Foreign Lawyers (LL.M.)

- Supplementary Studies "Labour Law, Organisation and Personnel Management

- Certificate Studies in "Energy Law

Profile in research

The research focuses of the individual chairs cover the entire spectrum of legal science. The profile of the Faculty of Law is formed on the one hand by the basic subjects, which are represented in Jena in all their diversity (legal methodology, legal theory, philosophy of law, history of law, sociology of law as well as key qualifications).

On the other hand, the faculty is characterized by a strong and broad profile in business law. Besides business law, we also place weight on labour law and interrelated subjects, especially criminal law and social welfare law.

Feuerbach-Day

"Style is the proper omission of the unimportant."

Paul Johann Anselm Feuerbach

The birthday of Paul Johann Anselm Feuerbach, who obtained his academic education at the University of Jena and then taught there as a professor, is the occasion for the annual academic ceremony of the Faculty for the festive presentation of the doctoral certificates.

This takes place after a lecture in the auditorium of the main building of the University and is framed by a musical programme. Afterwards, a reception takes place in the Senate Hall, giving the doctoral students, their parents and friends the opportunity to network and also to get to know the professors supervising the work.

The Feuerbach Day is supported by the "Alumni of the Faculty of Law of the FSU e.V.".